Anyone who has taken an interest in the practice of field recording has probably noticed the extremes that artists have gone to in the past ten to fifteen years to document difficult and remote locations.

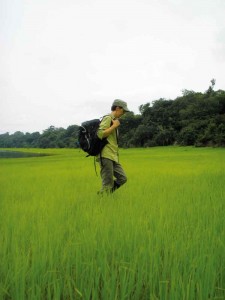

Camilla Hannan recording in the Amazon. Image courtesy the artist. Photograph by Stefano Tedesco.

Some significant CDs to emerge from this burgeoning trend include Antarctica (1988) by Douglas Quin; Baikal Ice by Peter Cusack (recorded at Lake Baikal in Siberia), Arctic by Max Eastley, and Wind [Patagonia] by Francisco Lopez. CDs such as these provide an insight into remote and inhospitable environments that are usually inaccessible to the rest of us. The recordings are often evocative, atmospheric and strange as faraway environments are probed for specific signifiers that mark them with a highly unusual sonic and spatial imprint.

As someone who has enjoyed the work of these and many other sound artists investigating similar concepts, I have started to wonder about the logistical and philosophical underpinnings of this very hazardous art practice. What is it about these types of locations that makes them so attractive, and what are the challenges that have to be overcome in order to operate there? On one hand I am curious about the physical and psychological demands that must be met in adapting to environments that can range from extremely hot and humid to extremely cold and dry, not to mention the technical challenges that must be overcome to produce a useful artifact. On the other hand I wonder how truly distinctive some of these remote environments are from those more common and readily available. For instance, how do we differentiate common atmospheric conditions such as precipitation and wind to arrive at a specific reading of a place different to another? How well does field recording capture the spaces and resonances of a particular location to arrive at a unique experience, or does the experience hinge on a conceptual premise to remove any perceived ambiguity embedded in the recording?

In order to get to the bottom of some of these questions I have asked some of the leading practitioners of location field recording [Chris Watson, Douglas Quin, Camilla Hannan and Max Eastley] to share their experiences to reveal the rationale behind their practice and what they discovered about themselves when confronted with an inhospitable landscape.

[For more, read the special Arts of Sound November 2009 Issue of Art Monthly Australia www.artmonthly.org.au]

Philip Samartzis

Phillip Samartzis is a Melbourne based sound artist and the recent recipient of an Australia Council project fellowship to travel to Antarctica.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.