In the short time span of a few months the media landscape of Los Angeles has undergone a major transformation:

with astonishing speed the traditional billboards — long a staple of the cityscape of La La Land — have been replaced with dynamic LED-billboards. Hundreds of them have already been installed, and more are on the way.

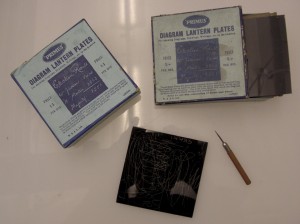

Set of Primus Diagram Lantern Plates ”For showing Diagrams, Drawings, Writings, etc. in the Lantern”. William Butcher and Son, London, c. 1900 (author’s collection).

LED-billboards extend the principle of “heavy rotation,” familiar from commercial radio and music television, to the public urban environment. The thousands of back-lit LEDs glow with power that makes the messages visible in the brightest sunlight, not to say anything about the night.

Indeed, those who are unfortunate enough to live right under their glow — and the number of such citizens is rapidly growing — have begun to experience “false sunrises” and demand public regulation (something that has never worked in L.A., where thousands of illegal billboards persist in spite of repeated official orders for their immediate removal).

Despite being the newest of the new and a consequence of recent advances in LED lighting technology (that is already beginning to affect private interior spaces as well), there are historical precedents that are worth excavating. Such an endeavor amounts to an “archaeological dig of the public media display.”

In ‘light’ of these recent developments, Albert Robida’s 1883 description of the effects of the two “immense glass plates, twenty-five meters in diameter,” he imagined erected on both sides of the building of L’Epoque (the audiovisual newspaper of the future) seem prophetic. According to Robida, they “resembled two moons, particularly after dark, when an electric spark made them shine against the dark background of the sky.”

In Robida’s vision, one of these public ‘proto-screens’ would be dedicated to advertising, while the other would display news transmitted in real-time from around the world. The news-feeds were to be sent by L’Epoque’s roaming reporters by means of portable ”telephonoscopes” that anticipated to a surprising degree the compact satellite transmitters used by today’s war correspondents.

When it came to the ’advertising channel,’ a calligraphist was supposed to draw the ads on paper and an “ingenious electric apparatus” would reproduce them on the glass plate in “gigantic characters.” This idea is not as fantastic as it may seem as magic lanterns had already been used for similar purposes for some time. Although billboards were also making inroads into the urban environment, it could be claimed that the dynamic media billboard had its origin in outdoor magic lantern projections.

Tradecard for The Automatic Stereopticon Advertising Company, Boston, c. 1860s (author’s collection).

In Boston a company promised already in the 1860s that its “Automatic Stereopticon Advertiser Works All Night,” displaying “your Advertisement to wondering crowds.” The trade card displays a large magic lantern placed on a scaffolding in a town square, projecting the company’s name and address on a large screen erected on a horse-drawn cart. Although it is night, a large crowd of spectators is present (so the promoter would like us to believe).

Besides advertising, outdoor magic lanterns were used for public election night projections, particularly in the US. The latest counts, received by the telegraph and rapidly scribbled with a needle-pointed stylus on black-coated lantern slides, were projected on huge screens erected on rooftops. No doubt, here is the model for Robida’s ‘advertising channel.’

From having been focused on walls and rooftops the projectors were soon tilted even higher. In his own version of the newspaper of the future, The Earth Chronicle, Jules Verne included a ”sky-advertising department.” It had “a thousand projectors” engaged in displaying “mammoth advertisements” upon the clouds. The eccentric British inventor H. Grindell Matthews, known as the “Death Ray Man,” tried this in practice in the 1930s, but did not progress beyond prototype demonstrations.

In 1873, Auguste de Villiers de L’Isle-Adam suggested ironically that even the moon could be inscribed with an advertising slogan. For some, this may ring a bell: in 2008 the brewing company Rolling Rock promised to do the same for its logo.

The exhortation to have a good look at the next full moon, repeated on many “Moonvertising” billboards throughout L.A., was a hoax, but it created plenty of buzz on the Internet, which of course was the purpose.

As these examples show, both the public implementation of technological innovations like super-bright LED-displays, as well as the discursive ideas surrounding them, are deeply rooted in media-archaeological layers of forgotten data. As we finetune our strategies to defend ourselves against these latest assaults on our ”vision rights,” we might just as well look for support from the past by analyzing the rich arrays of experiences – both imaginary and real – lying buried in cultural archives.

Copyright © Erkki Huhtamo 2008

Erkki Huhtamo

Erkki Huhtamo is a media-archaeologist. He was born in Helsinki, Finland in the last millennium. He has a Ph.D. in cultural history and works as Professor of Media History and Theory at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), Department of Design | Media Arts. His work has explored many aspects of media history and the media arts. He has just finished a book on the history of the moving panorama and the diorama (University of California Press, forthcoming 2009) and is editing a collection of essays on media archaeology (with Jussi Parikka, California University Press, 2009).