Artists are creative, warm hearted, free and value beauty, while scientists are cold, objective, love precision and are constrained by rationality. Right? Well the general acceptance of such dramatic divides between people engaged in art and those engaged in science certainly permeates much of our culture. But where did this idea spring from?

The division between artistic and scientific activities as we know them began with the scientific revolution of the 1700s. The word ‘art’ is itself relatively new, dating back perhaps only a couple of hundred years. But it was in more recent times – 1959 to be exact – that the divide between the cultures of science and the humanities (including art) was so definitively expressed by scientist and novelist CP Snow in his historical lecture ‘The Two Cultures’. These perceived differences between art and science are perhaps a reminder of the Aristotelian distinction between aisthetá kai noetá – ‘felt’ versus ‘thought’ – or of the two Euripidian forces, the wine (emotions) and the bread (rational mind). [1]

There is on the other hand an increasing interest in the similarities between the cultural evolution of ideas and concepts in art and physics; the concept that they develop in parallel. For example, the idea – expressed in books by Arthur Miller and Leonard Shlain – that in the early 1900s both Picasso and Einstein were in search of the fourth dimension. [2,3]

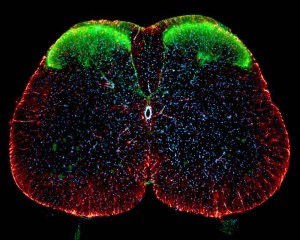

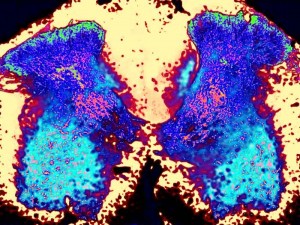

I will highlight here, from a neuroscience perspective, the similarities between these two, apparently opposite, activities and will argue that the difference between artist and scientists depends on subject matter rather than on brain processes. One obvious similarity is that both artists and scientists are, at their best when involved in producing something new. It is the novelty in an artistic piece that attracts attention and recognition. Similarly, scientists are recognised for their discoveries, not for their confirmation of previous findings.

While is well accepted that art involves imagination, manual skills and a sense of harmony and beauty, it is less acknowledged that it also requires method, rigor and discipline.

Similarly, scientific discoveries certainly require method, rigor and discipline but also call for manual skills and are often driven by a desire for harmony, from which a sense of beauty is generated.

Art and science alike involve curiosity, imagination, self-criticism and skepticism, discipline and manual skills, empirical testing, a sense of harmony and pleasure, and both are eminently social activities. These are all high brain functions that appeared in evolution with clear advantages for humans, and are thus well embedded in the neural circuits of our brains.

Curiosity is a major driver, equally in the creation of an art piece and in the search for what is behind processes in nature. As an engine for exploration and exploratory behaviour, curiosity, emerged with the earliest mammals. In humans, however, the specific drive to look for what is behind, say a forest, a desert, a hill or a stretch of water, underpins our remarkably successful migration to all corners of the Earth over the past 100 thousand years. We would describe it as a search for the unknown.

Imagination can be regarded as the ability to go beyond the here and now. While the brain is dedicated mainly to ensuring the survival of an organism in the face of constant immediate change in its environment, the increased ability to imagine what might indeed lie behind a hill etc, became an essential advantage. Armed with this greater ability to imagine what lay beyond their immediate vicinity, the first explorers during early human migration out of Africa succeeded in populating new lands. In more recent times, such exploration has increasingly shifted away from simple geographical exploration to encompass any hidden aspect of the world, be it in the natural world (science) or in the world of inner experiences (art). Neuroscience experiments are providing ample evidence that when we simply imagine something the part of the brain usually involved in seeing is activated, suggesting that imagination is a kind of extension of vision. Imagination involves the very brain regions (and probably the processes) involved in the memory of past experiences.

Skepticism: One of the foundations of science is its remarkable ability to self-correct; whereby the exciting feeling of a ‘eureka’ moment is balanced by a sobering feeling of doubt. Many great discoveries were made by scientists who doubted their own observations or interpretations. Is it really so and so – asks the skeptical scientist? Are things what they appear? Naturally, this skepticism of ideas and findings extends easily to the ideas of others scientists. Is there any equivalent to skepticism in art?

A sense of incompleteness or dissatisfaction when finishing a painting is a common driver for an artist to retrace their steps and often to redo an entire canvas in search for perfection. The sense that ‘this is not good enough’ or ‘this is not what I had in mind’ permeates artists’ lives. The sense of doubt in the exploratory activities of both artists and scientists suggests that the need for inner satisfaction is essential to both activities. Inner pleasure involves the emotional brain, from the primordial sense of safety and satisfaction of bodily needs at the level of the amygdala, to the higher levels of aesthetic satisfaction distributed in different cortical areas.

Indeed the search for harmony and beauty has traditionally been attributed mostly to art. Yet the history of science is full of explicit mentions of harmony and beauty as drivers for discovery. There is a growing interest within neuroscience circles on the ability of the brain to detect constant patterns and to derive pleasure from these. Perhaps the aesthetic aspects of both art and science reveal the common drive to make order out of the unknown and new, and to derive emotional pleasure from it.

Dissatisfaction with an art creation or a scientific work necessitates ways in which to remove uncertainties in order to enjoy the aesthetic pleasure. Trial and error appears to be the strategy that both artists and scientists alike have developed to avoid ongoing uncertainty. In the history of science this is known as the empirical method (experimental method), based on the experimental testing of any idea. This experimental method makes science a powerful self-correcting human activity. Art is above all also an empirical activity based on trial and error. Both art and science are constrained by the need to live in the real world of experience, which is what the brain has done so successfully during the process of evolution.

Discipline involving visuo-manual skills is required equally by artists and scientists. Learning to manipulate tools at the higher levels of both often requires many years of dedicated effort. These skills are the extension of the primitive tool-making skills of early hominids.

Both art and science are eminently social activities, sharing a main and deep desire for cultural interchange and the giving of one’s objects of creation as gifts to others. It is only relatively recently that art and science have acquired added ‘usefulness’ values.

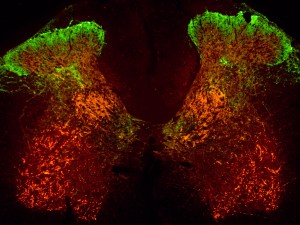

One remaining so-called difference between art and science and one that needs to be dispelled is the belief that art involves more the right brain and science more the left. There is indeed ample evidence that the two hemispheres perform different functions, with the right brain more suitable for spatial tasks and the left for sequential ones. These differences affect most human activities – from navigation to language and music – but it is also increasingly clear that all these involve all specific features of brain features. For example, language is not only made of sequences of perfectly timed words (left hemisphere), but requires also suitable intonations (prosody; right hemisphere). Listening to melodies and harmonies – recognising pitch, tones and beat – activates specialised areas of the cortex, which are also involved in listening to and understanding words, rhymes and intonations.

The specialisations of the two hemispheres are used in full in both artistic creativity and scientific discoveries and remind us that they are both the result of the creative abilities of the same one, complex and wondrous brain. It is of no surprise if more artists and scientists find much to share.

They are both explorers of the unknown.

Professor Marcello Costa

Professor Marcello Costa is a founder (and one-time President) of the Australian Neuroscience Society (ANS) and a founder of Neuroscience. Currently Professor of Neurophysiology at Flinders University and co-chair of the South Australian Neuroscience Institute (SANI), he is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science and a Centenary Medal awardee. Marcello combines his passion for investigating the nervous system with educating generations of students and championing public education in neuroscience.

References

[1] Susan Greenfield (2000). The private life of the Brain. Penguin books.

[2] Arthur Miller (2001). Einstein, Picasso; Space Time and the Beauty that causes havoc. Basic Books.

[3] Leonard Shlain (2007). Art & Physics; Parallel visions in Space, Time, and Light. Harper Perennial.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.