David goes to work: The pvi collective have a long standing pre-occupation with producing artwork that investigates invisible invasive technologies, the morality of surveillance in the name of security and safety.

Photo: Tamara Dean

We’ve been producing a body of work under the banner of panopticon for some time now, questioning our relationship and dependence on technology as a provider of a (false) sense of security.

The original format for these live art works would be a networked performance of some kind, back into a venue, using projection and sound as a window onto unfolding activities on the streets outside. We would find ways for performers inside to interact with performers and people outside, placing the audience in that uncomfortable position of watching and listening, questioning is this a performance or is this real? Is the use of surveillance technologies right or is it wrong? And what is this huge grey area in-between?

Pvi reversed this format, with a series of new panopticon works, panopticon: taipei, panopticon: perth and panopticon: sydney. We decided to abandon a performance venue entirely in favour of constructing a new space and working directly with a small number of people, outdoors, on the streets. The framework was to offer a privacy service, to provide a mobile private space, to appropriate eight umbrellas into a customised cocoon, for 5 individuals in each city visited. As a tactical privacy tool, utilising these umbrellas completely shields a passenger from the outside, leaving them anonymous but also blinded, unable to see. Our pvi privacy team navigates them via CB radio, carefully guiding them on a journey in public spaces monitored by CCTV cameras. It is, of course, an absurd reaction, an eccentric act of performance, but part of our way of working is to tackle serious subject matter with an element of humour.

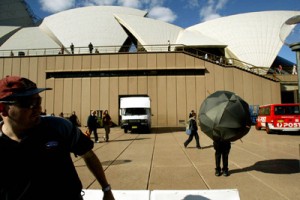

We see these works existing as two parts: live events and a sculptural installation, using the audio and video documentation from each journey. For panopticon: sydney our start point was outside the front of the Museum of Contemporary Arts and the journeys would all unfold around The Rocks and Circular Quay area, which has an extensive high tech CCTV network, alongside security patrols. Our five journey tasks were to post a letter, browse the markets, catch a ferry, meet a friend for a drink and go to work.

Interestingly in Sydney, the experience was very different for us (to the works made in Perth and Taipei). Navigating passengers was still arduous, ensuring their safety at all times as they hop onto an escalator, walk the cobbled paths around The Rocks, or climb a narrow platform onto a ferry. But something else happened in Sydney; the increased security and sense of paranoia around icons like the Sydney Harbour Bridge and The Opera House, intensified the difficulty for us in ways we hadn’t expected.

David goes to work was our fourth journey. We had encountered previous security problems to that point, as we hadn’t notified anybody of what we were doing. From our point of view, we were providing a privacy service, it was an agreement between pvi and our passengers to do our utmost to get them to their chosen destinations and we were simply providing a private space for them to do it – we thought that shouldn’t be a problem. We did have a number of strategies for dealing with security officials though. One was to smile a lot! The other tactic was to split up. Because we were equipped with two cameras, we decided that one could stay and deal with any problems and the other would attempt to continue with the umbrella cocoon, filming both events in the process. We were quite keen for it to be a pleasant experience for our passengers inside, so we had this strange dilemma of trying to keep things enjoyable, whilst trying not to panic as things started to go wrong (which inevitably they did) and that is primarily the point of this work. Its failure to succeed in what was a basic everyday task highlighted the issue of surveillance, security and access to and what is deemed to be appropriate behaviour in public spaces.

Photo: Tamara Dean

David goes to work started out pretty well, the sun was shining, kids were patting the cocoon as it proceeded along the quayside, tourists were spinning their camcorders and mobile phones around filming and photographing us. “Are you with Rove Live?” one woman asked Steve. “Yes” we replied, smiling and moving on. We walked out to the main road and straight into the path of an oncoming Rocks Security Ranger, whom we had encountered previously in the week. The Security Rangers were of the opinion that we should be applying for a permit for ‘this kind of thing’, which we were quite confused about, but had promised to look into it. They begrudgingly let us proceed earlier in the week, assuming it was a one off ‘occurrence’ and we seemed harmless enough, what with all the smiling and all. This was clearly not going to be the case today. Straight away he held out his hand and asked to see our permit. I have to say that we did look into permit applications from the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority and had decided that we weren’t buskers, we weren’t asking for money from anybody, we weren’t performing or making a movie, so didn’t feel that it applied and explained this to the ranger. His response was to suggest that we stop right now. If we didn’t have a permit, we couldn’t proceed. At this point we tried to get to the heart of the matter and asked if it was the cameras that were the problem. He replied yes, it was the cameras and we should switch them off immediately. We considered politely pointing out that we had just passed quite a few other people with cameras and maybe he’d like to request a permit from them also, but we were happy to compromise and said that if it helped, we would switch the cameras off and continue on our way if that was ok. It turned out that wasn’t ok. It wasn’t just the cameras; it was the actual activity. We simply wanted to take David to work, we said, what’s wrong with that? At this stage we should point out that David worked at the opera house, he is a part time mechanist there and has a security pass to access the premises. The reply was that it was possibly a safety issue and that if a member of the public were to suddenly run and impale themselves onto one of the spokes of the umbrellas, they would be liable and that wouldn’t be a good thing. This was a fair point, but having not seen any indication of kamikaze tourists so far, it didn’t seem likely.

We hit a bit of a stale-mate at this point, so thought the best thing to do would be to try to find out the consequences of what would happen if we didn’t stop. Would we pay a fine or be arrested? The Ranger wasn’t able to tell us what would happen, but he was keen to point out that there would be consequences if we were to proceed. So we said “well, maybe we’ll just carry on and find out what those consequences are when we get there”.

He stated that in that case, he would have to monitor us. We thought this was great! So we asked if he maybe would like to help us? If he was concerned about safety or security, then an escort would be a terrific way to help. He seemed quite insulted at this suggestion, but monitored us as we made our way to the Opera House, where there was this security change (presumably between the Ranger’s jurisdiction and Opera House Security). There was a lot of talking back and forth into their walkie-talkies. We had walkie-talkies too, so we decided to do the same. Steve got held up at that point and was told that his camera was ‘too large’, so we carried on, only for me to be stopped in the middle of the forecourt by a slightly chubby guard with mirror shades. and his tactic was remarkably similar to my own (which was to smile a lot), so we had this strange kind of smile-off where he was standing in front of me smiling and I was smiling and neither of us were actually getting anywhere… except for James who continued to navigate David towards the employees’ entrance.

Security staff that the best course of action was to call for re-enforcements, which surprisingly came in the form of marketing executives who came down quite flustered, waving a business card and an application form and proceeded to gently reprimand us on not having followed the correct procedure. If only we had called them first, if only we had gone through the proper channels, made an application, indicated our shot requirements, booked a day that was suitable and of course, provided them with our $10,000 public liability certificate, none of this would be a problem, you understand?

Yes, we understood, and that was as far as we got. David gave up at the prospect of getting into work. He ended up sitting on a bench outside the entrance and tucked into a vanilla slice that we had stopped and purchased on his journey. Fifty-five minutes had lapsed since leaving the MCA front door. We made our way back to store the cocoon and were followed by two plain-clothes gentlemen, who upon entering the MCA approached and asked us if we were planning to go outside ‘in that contraption’ again. We replied, no, we had finished for the day, thanks. Their reply was that if we were to leave the building again ‘with that thing’ we would be slapped with a court order and a $4,000 fine each. A little taken aback, we asked who they were. Were they with the opera house? They refused to give their names, said they were with the federal government and gave us a badge number. Badge number 61. Apparently that was all we needed to know.

pvi collective

Kelli McCluskey and Steve Bull are the co-founders of pvi collective, a West Australian based New Media collective.

panopticon: sydney was exhibited at Primavera 04, Museum of Contemporary Arts in Sydney, 2 September – 7 November 2004.

pvi would like to extend grateful thanks to Fiona, Steve, David, Karen and Catharine for participating in the privacy service in Sydney.

Read More

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Australia.

[...] https://filter.anat.org.au/issue-58/pvi-collective-panopticon-sydney-2/ [...]