Graffiti is a very serious crime. More serious than armed robbery. More grievous than murder. More grim than biting the heads off baby chickens! Well, perhaps not in real life, but in my world it is.

In our shared western world, elected politicians, judges and courts determine and determine the rules of crime and punishment. The system has at least a thin veneer of democracy. In my world, the world of “interactive entertainment”, it is large corporations and state bureaucracies who judge criminals and prosecute crimes – crimes that take place within videogames.

In 2006, the game Mark Ecko’s Getting Up: Contents Under Pressure was banned for sale in Australia by the Australian Office of Film and Literature Classification. The reason given was that the game featured and encouraged the illegal act of graffiti. It is challenge to follow the moral logic behind the banning of the game. Perhaps where we once feared for an entire generation of children growing up desensitised to violence (a wholly unproven yet nevertheless fascinating notion) we now face the terrifying prospect of children becoming desensitised …to graffiti.

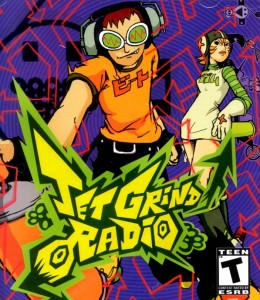

Sega's Jet Grind Radio on the Dreamcast comprises of radical rollerblading dudes and dudettes zooming around the futuristic city Tokyo-to spraying walls to defeat proponents of an oppressive and corrupt government.

Or perhaps the mere combination of these two great social ills – graffiti and gaming – is enough to incite whole new levels of censorious hysteria. Is it the case in the judgment of Getting Up, whereby the Australian Film Classification board decided that the real social risk posed the by game’s perceived lethal cocktail of gaming and graf was too high? Obviously these board members were not the same who approved a similarly justifiable virtual risk to society, Grand Theft Auto.

But how radical and anti-establishment is this combination, really? Radical doesn’t look so radical when a major entertainment corporation and a mainstream fashion label start sponsoring and cheerleading your rebellion. The marketing spin is that games like this (there are many games featuring the act of graffiti in gameplay) celebrate and legimitise graffiti as an art form. But I wonder if these terms are just euphemisms for “coopt and sanitize”. Graffiti in games and fashion could be like what punk was in the 90s: a style lingering long after the substance has evaporated.

It probably has various meaning to different people, but for me (as the friend who helps carry paint and looks out for cops, rather than actually doing the business) the soul of this street art form is in its blunt challenge to the sanctity of private property, and its unapologetic sense of entitlement to public expression. It is a handcrafted, personal gesture that cuts across the soulless, slick fonts and computer-aided, mass-produced imagery that dominates public space. However, once it’s been mass-produced and sold to me by a big corporation in a conveniently sized box to be enjoyed within the comfort of my living room, I’m not so sure what it means anymore.

If only game development could be more like graffiti art. The recent socio-political climate of inner city Melbourne, including a lax approach to the discouragement of graffiti, it is not too hard to go out and find a space to take control of for a while and make it your own canvas. And as a mode of distribution for ideas, it’s pretty simple and effective. Melbourne’s altered, decorated and ideas coated laneways have also become a tangible tourist attraction. It is not difficult, on any given day, to explore these spaces and view the interventions that have been made, and also to see other people eagerly doing the same. Every Saturday sees wedding parties gleefully posing for photographers in graffiti drenched Hosier Lane, every other day sees Japanese tourists and locals alike, doing the same.

On the other hand in the game industry, the biggest canvases – PlayStation, XBOX, Wii, DS – are owned and controlled by Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo. You need permission to write on their walls. Your unapproved work could potentially damage their (intellectual) property, so they make sure it’s far from easy for you to create and distribute outside of their tyrannical control.

Within game environments, what may superficially look like public, community space (for example a persistent world within a massively multiplayer online game such as the World of Warcraft, or even a fairly open virtual community like Second Life) is not actually genuine public space at all. It’s privately owned and policed by corporations. Within games, the actions of players are naturally constrained within hard-coded rules. The rulers of these communities may often be benign dictators, but they are dictators nevertheless. There are few examples of digital uprising and resistance towards these autocrats.

As citizens of online gaming environments our right to freedom of expression is token at best. While protests and demonstrations are held from time to time to send a message to the powers that be, but you could say the same of countries run by military dictatorships, such as Burma.

One example of game space disruption was actually based on the use of in-game graffiti. In 2002, a group of artists initiated an artistic and political game intervention they called Velvet Strike. They provided people with anti-militarist graffiti designs and encouraging them to invade Counter-Strike game servers simply to spray these designs around the environment during gameplay. While this was mildly disruptive to the games themselves, it didn’t break the rules, so the artists couldn’t be banned from the game servers.

But graffiti in real world space pretty much always breaks the rules. Out there on real walls it’s still a very much an illegal, powerful act. May it continue to be so. May graffiti forever challenge corporate property, not become corporate property.

Katharine Neil

Katharine Neil is a game designer who has worked in commercial game development in various roles since 1998. In her non-professional guise she was Creative Director of the Escape From Woomera game project in 2003, and with Marcus Westbury in 2004 she founded Free Play – Australia’s annual independent game developers’ conference. Occasionally her rants about games, politics and culture are published, but when they’re not they end up on her blog.

Read More

http://kippersmightypen.blogspot.com/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.